The Feed Iceberg

What on Earth is it?

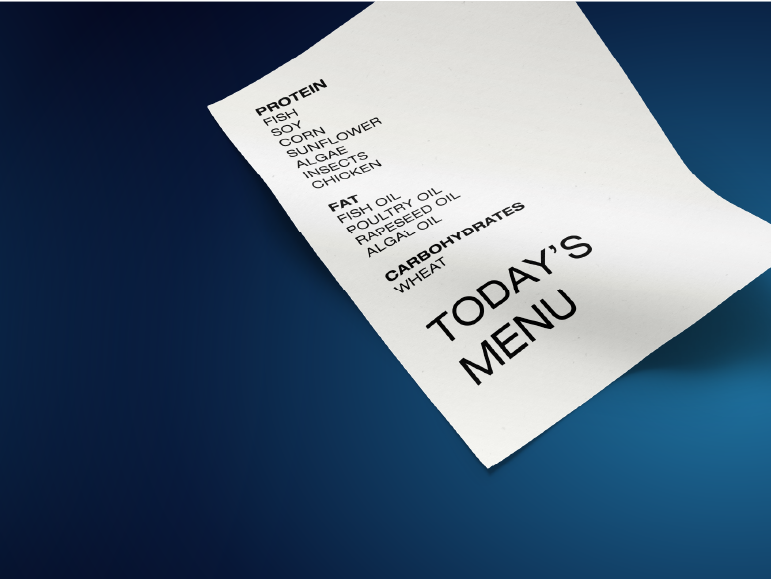

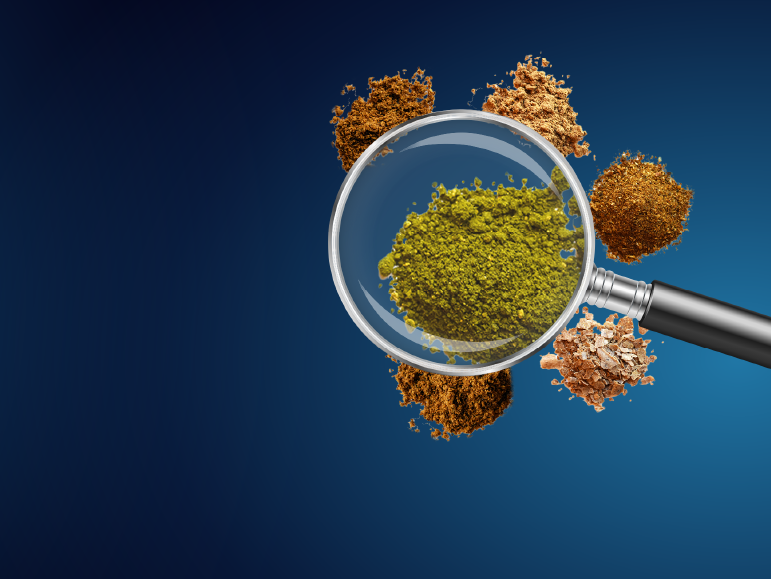

Fish and shrimp feeds are an essential contributor to global food security. Every day, Skretting feeds contribute to over 21 million seafood meals around the globe. There is a lot of outdated information about feed out there, but the industry has come a long way from where we began. So, what is in a feed? How do we make them? How do we ensure quality and sustainability standards? And why do they cost what they do?

Did you know that over 20 million people around the world work in aquaculture, and the animals they feed all depend on these little pellets? As a global feed producer, Skretting has a huge responsibility, and we are passionate about getting it right.

One of our ambitions is to make sure that we are transparent in what we do, so that people can feel secure in buying and eating farmed fish and shrimp (side note, did you know that over 50% of all seafood is farmed, and that wild catch has not increased since the 1980s?). For that reason, in this series, we shine a light on our aquaculture feeds, their unique properties, and the innovation that is critical to ensuring we can all enjoy safe, healthy and sustainable seafood in the future.

Read on to learn about the highly advanced processes behind the humble but mighty pellet.

Why the feed iceberg?

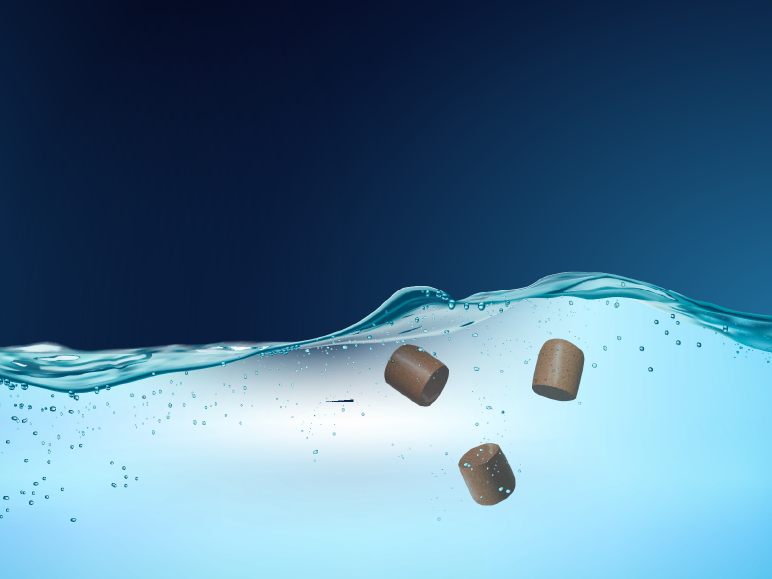

In the same way that 90% of an iceberg is hidden below the waterline, almost all the value of aquaculture feeds is not visible to the naked eye (let alone people outside our industry). We want to change that. The humble pellet exterior hides decades of boundary-breaking scientific research and development, and practical commercial application – all geared towards making the farming of aquatic species more available, sustainable, productive, and valuable.

Next

A little background and the future of blue food. Otherwise known as ‘why Skretting exists’

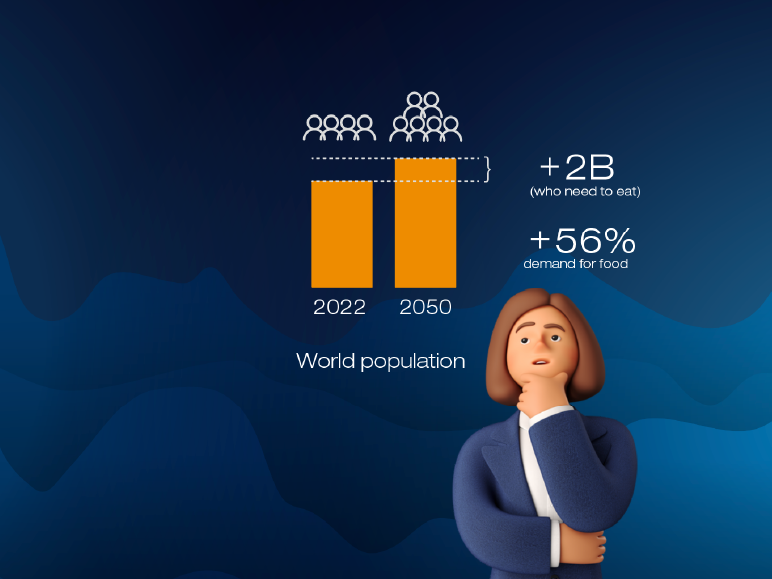

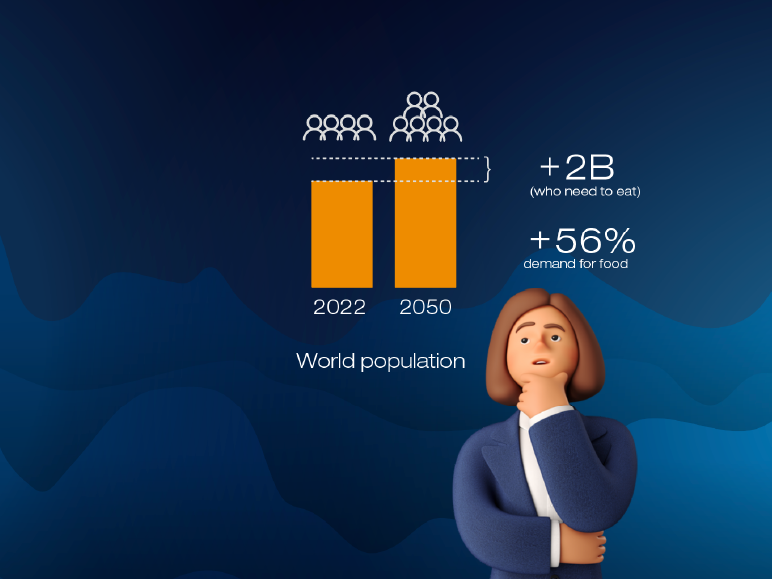

Before we dive into the pellet itself, let’s talk about why we’re here. The global food security challenge is straightforward and well-known: by 2050, the world must feed two billion more people, an increase of a quarter from today’s global population. The demand for food will be 56% greater than it was in 2010. This needs to be achieved with no more land and limited fresh water.